Facturatie 2025

De opgave van uitleningen over 2024 is afgerond. De cijfers zijn te raadplegen: via de button Inloggen hier rechtsboven op de homepage kan iedere bibliotheek naar de eigen portalpagina om de opgave te bekijken.

De tarieven van 2025 zijn vastgesteld door het bestuur van de Stichting Onderhandelingen Leenvergoedingen (StOL) in zijn vergadering van 11 maart 2025. De tarieven 2025 worden gebruikt voor de factuur 2025 die u binnenkort krijgt, gebaseerd op uw opgave.

Met het betalen van de factuur 2025 voldoet u voor dit jaar aan uw verplichtingen voor het leenrecht.

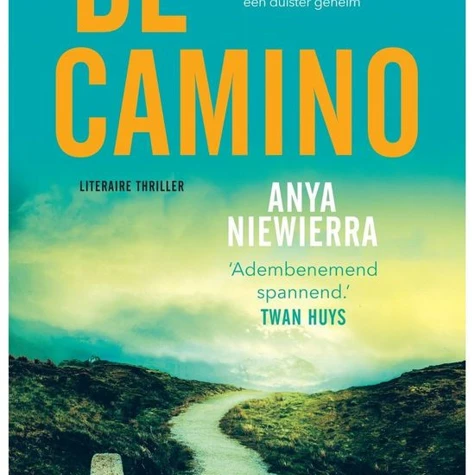

Top 100 uitleningen 2024

De titels uit de Online Bibliotheek domineren de lijsten van 2024. Het meest geleend was opnieuw De Camino, van Anya Niewierra (Uitgeverij Luitingh-Sijthoff), maar ook de nummer twee uit de Top 100 was van haar hand: Het bloemenmeisje.

Beide titels hadden hun hoge notering te danken aan de uitleningen in de digitale bibliotheek. Het meest uitgeleende papieren boek was net als vorig jaar Lucinda Riley's Atlas, het laatste boek uit de succesvolle serie De zeven zussen (Xander Uitgevers).

Een oude bekende, De waanzinnige boomhut van 130 verdiepingen van Andy Griffiths en Terry Denton (Lannoo) was het meest populaire kinderboek, op de 12de plek.

Een voorlopige schatting van het totaal aantal uitleningen in de openbare bibliotheek komt op 52 miljoen papieren boeken, een lichte stijging ten opzichte van het voorgaande jaar. De uitleen van e-books steeg naar 5,8 miljoen. Audiobooks kwamen tot een totaal van 2,6 miljoen.

Een voorlopige schatting van het totaal aantal uitleningen in de openbare bibliotheek komt op 52 miljoen papieren boeken, een lichte stijging ten opzichte van het voorgaande jaar. De uitleen van e-books steeg naar 5,8 miljoen. Audiobooks kwamen tot een totaal van 2,6 miljoen.

Bekijk hier de volledige CPNB Top 100 Uitleningen 2024.

Leenrecht op scholen

05-02-2025

In het verleden was er onduidelijkheid over de toepasselijkheid van het leenrecht bij uitlenen op scholen. Onderwijsinstellingen waren vrijgesteld van de betaling van de leenrechtvergoeding. Maar wat als scholen samenwerkten met openbare bibliotheken, die wel leenrecht moesten betalen? De staatssecretaris van OCW heeft aan die onduidelijkheid een einde gemaakt door te bepalen dat de wet zal worden aangepast.

In de toekomstige structurele situatie ontvangen rechthebbende auteurs en uitgevers een vergoeding voor de uitlening van hun boeken via bibliotheken op scholen ongeacht de soort bibliotheek. Daarvoor wordt de Auteurswet gewijzigd. De onderwijsvrijstelling komt te vervallen voor scholen voor PO, VO en MBO, maar de vergoedingsplicht neemt het ministerie op zich. Daarmee wil men voorkomen dat het onderwijs administratieve en financiële lasten zal ondervinden.

De aanpassing van de wet valt samen met de aanpassing van de Wet Stelsel Openbare Bibliotheekvoorzieningen, die gepland staat voor juli 2026. Tot die tijd maken OCW en Stichting Leenrecht apart afspraken over vergoedingen voor uitlenen op scholen. Deze afspraken worden per jaar vastgelegd in een convenant en gepubliceerd in de Staatscourant.

Om de hoogte van de vergoeding te bepalen heeft OCW onafhankelijk onderzoek gedaan naar het aantal uitleningen op en door scholen. Daarbij was onder andere van belang of de boeken de school verlaten.

Ten behoeve van dit onderzoek heeft Stichting Leenrecht op de opgaveportal een extra scherm toegevoegd, de categorie Uitleningen op school. In deze categorie kunnen bibliotheken alle uitleningen opvoeren die zijn uitgeleend op en door scholen, in het kader van dBos of een andere samenwerkingsvorm tussen openbare bibliotheek en school. Het gaat om uitleningen die zijn geregistreerd in het systeem van de openbare bibliotheek, waarbij het niet van belang is of de boeken eigendom zijn van de bibliotheek of de school.

De uitvraag gebeurt op vrijwillige basis en dient enkel voor het verkrijgen van inzicht. Het tarief voor de uitleningen in deze categorie is 0.

Het uitlenen van E-books

17-02-2025

Het lenen van e-books werkt anders dan het lenen van papieren boeken.

Kan ik een e-book lenen/uitlenen?

Je kunt e-books bij de bibliotheek (een publieke instelling zoals genoemd in de auteurswet) lenen. Dan krijg je een tijdelijk bestand wat na een bepaalde periode automatisch onklaar wordt gemaakt zodat je het niet meer kunt lezen. Dit wordt een tijdelijke terbeschikkingstelling genoemd. Je betaalt via je abonnement bij de bibliotheek aan de uitgever en auteur die per gelezen e-book een billijke vergoeding ontvangen.

Je mag zelf geen e-books uitlenen. Enkel publieke instellingen zoals bibliotheken kunnen uitlenen volgens de auteurswet. Jij als persoon bent geen publieke instelling maar een individu. Daarnaast zit er geen tijdelijke beperking op als je een e-book “uitleent”. Feitelijk kopieer je dan het bestand voor onbepaalde tijd. Met het maken van deze kopie “verveelvoudig” je het werk. Dat is volgens de wet enkel voorbehouden aan de maker (afgezien van enkele uitzonderingen).

Rechtspraak E-books

In een arrest van 10 november 2016 heeft het Europees Hof van Justitie bepaald dat onder omstandigheden e-books net als gedrukte boeken onder het wettelijk leenrecht kunnen vallen. Daarvoor zou de overheid dan wel eerst de wet moeten aanpassen. In plaats daarvan hebben de betrokken partijen in Nederland afspraken gemaakt over het uitlenen van e-books. Het uitlenen wordt nu centraal georganiseerd door de Online Bibliotheek. Deze collectie biedt een ruim aanbod van digitaal uitleenbare e-books en e-luisterboeken. Deze dienst staat los van het leenrecht.

Meer informatie?

Bel Arjen Polman 023-7997012 of mail leenrecht@cedar.nl